Why do we still type on QWERTY in the 21st century, even though this layout was born in the era of mechanical typewriters and is not considered the most ergonomic? Let's look at how a historical incident turned into a habit, why protests in favor of Dvorak and Colemak died down, and whether there is any chance at all for "smart" or neuro-layouts to change our everyday typing.

Advertisеment

From Typewriters to Screens

Have you ever wondered why your keyboard is designed this way? Not because it's convenient, but because in the 19th century, the mechanics of a typewriter simply couldn't work any other way.

The problem was in the levers: If you pressed adjacent keys too quickly, they would stick. And the letter positions remained the same despite the fact that typewriters grew into keyboards.

Christopher Sholes, a journalist and inventor, found a solution - he mixed up the letters so that frequently used combinations were on different sides. This slowed down the typing speed, but saved from jamming.Legend has it that the top row of QWERTY allows you to quickly type "typewriter" - supposedly this was a marketing ploy. But the reality is simpler: the layout appeared as a compromise between mechanics and speed. When the keys stopped catching on each other, QWERTY was no longer optimal. But it was not changed.

Why? Because millions of people got used to it.

By the 1980s, QWERTY had become a staple of computers. Manufacturers were in no hurry to switch to Dvorak or Colemak, even knowing their advantages. Ergonomics did not overcome inertia: changing the layout meant retraining users, breaking familiar patterns, wasting resources on something that did not bring obvious benefits.

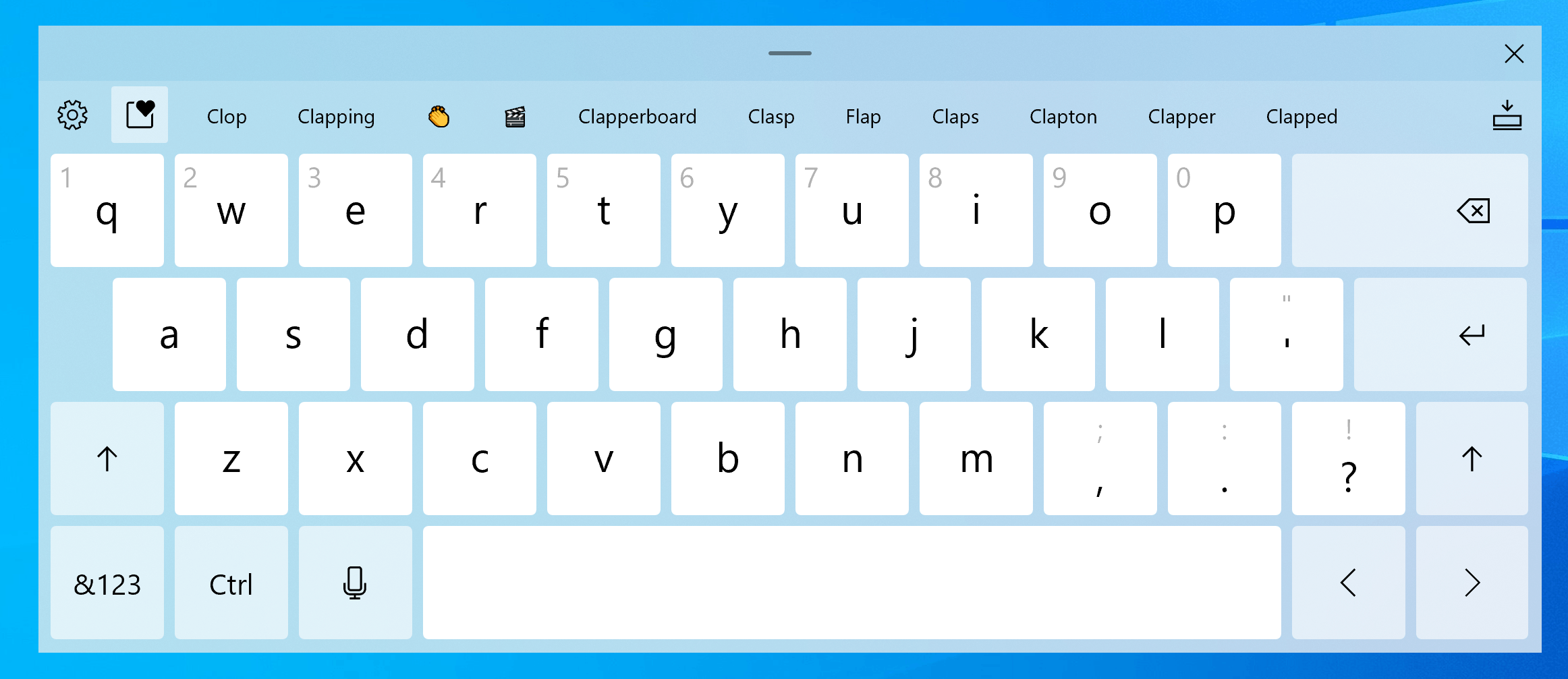

Now, when touch screens and voice assistants have long replaced physical keys on mobile devices, QWERTY still dominates. It survived not because of efficiency, but because of the widespread nature: The more people use it, the higher the cost of switching to something new.

However, we are already living in an era where physical keys are becoming a thing from the past. Smartphones and tablets have long since moved us into the touch space, and voice assistants are everywhere. What if the next "keyboard revolution" is not about the arrangement of letters at all, but comes in the form of an entirely new model of interaction with devices?

Imagine: You don't have to think about the layout, because you draw gestures with your finger in the air, and the system itself understands what you want to write. After all, there are already keyboards that can translate even the most indistinct whisper into text, Google's GBoard on Android, for example.

The "Most Effective" But Rarely Used Alternatives

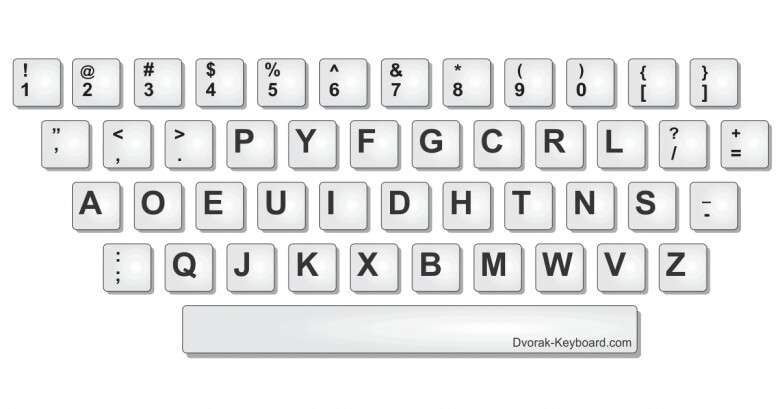

The Dvorak Simplified Keyboard (DSK), which appeared in 1936, promised more: 70% of the typing is on the main row, minimal finger movement, and reduced fatigue. Dvorak's research showed that his layout allowed beginners to achieve greater speed in less training time than on QWERTY. This approach made it possible to significantly reduce the distance that fingers travel during a working day: if on QWERTY it is up to 32 km, then on Dvorak it is only about 1.5 km.

Dvorak layout. Image by https://dvorak-keyboard.com/ .

In the early 90s, Barbara Blackburn set a world record for typing speed. Over the course of 50 minutes, she typed an average of 150 words per minute. The maximum speed reached 212 words per minute. This is faster than human speech. But to achieve such results, Blackburn abandoned the usual QWERTY layout in favor of the Dvorak keyboard.

A real cult formed around this typing method. But these successes remained in theory.

In addition, to reach the speed of 40 words per minute, a beginner on QWERTY needs an average of 56 hours of training, and on Dvorak - only 18 hours. You may not be surprised to learn that we are referring to decades ago. Naturally, every schoolchild today types faster.

The effect of the network standard turned out to be irresistible: at that time, many were already using QWERTY, and with each passing day, the cost of switching for each new user only grew. Even the recognition of Dvorak as an ANSI standard in 1982 did not change the situation.

By the mid-1980s, only about 100 thousand people typed on Dvorak, while QWERTY remained the only alternative for millions. The successes did not become widespread: tests proving the advantages of Dvorak were often funded by the inventor himself, and independent studies gave less impressive figures.

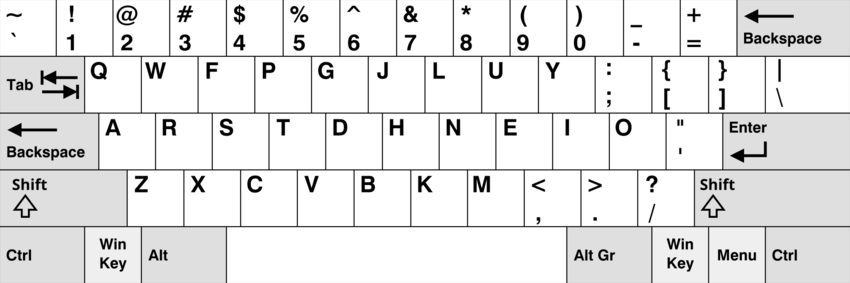

The Colemak layout, which appeared in 2006, tried to soften the transition. The author, Shai Coleman, changed only 17 keys compared to QWERTY to reduce cognitive and muscular "friction" during migration. Basic combinations like Ctrl+Z and Cmd+C were preserved.

This is not a revolution, but a compromise. Reduce finger movement, but do not break the usual hotkeys. However, even such a "soft" replacement faces barriers. There is no out-of-the-box support in the OS, not all drivers work smoothly, and in a corporate environment, where every project depends on standards, changing the layout is a risk.

Professional niches, such as programming, have their own options: Programmer Dvorak, Workman, Russian BAY and YAVERTY. They optimize the arrangement of symbols for code or language, but their audience remains narrow. And most projects, documentation and commands are still written for QWERTY. Nowadays, few people think about the layout, everyone is used to it, and do not even think that it could be different.

Why QWERTY is so resilient

The longevity of QWERTY is explained primarily by the powerful network effect and learning inertia. Over the course of a century and a half, this layout has become not just a standard, but a part of educational and corporate ecosystems Millions of people have gone through schools and touch-typing courses where training is based exclusively on QWERTY, and built-in simulators and lessons in operating systems and online services reinforce this skill from an early age.

For most users, the effort required to retrain muscle memory - even for a more efficient layout - often outweighs the potential benefits. The psychological barrier here is comparable to the need to relearn how to write over again. As a result, many prefer to stick with their familiar typing habits, despite the slower speed.

Corporate and technical barriers amplify this effect. Although Windows, macOS and Linux formally allow you to change the layout, in practice there are numerous pitfalls.

- Incompatibility with familiar hotkeys,

- failures in specialized software,

- and sometimes the impossibility of full support without third-party utilities like AutoHotkey.

QWERTY is built into everything from BIOS to cloud services. You can sit down at any computer and type "sudo" or "git push" without even having to worry about "Esc" or "Caps Lock". It’s not about convenience, it’s about compatibility.

If you suddenly switch to Dvorak and then get on someone else’s laptop, are you ready to spend half an hour searching for the right letters or will you just go back to QWERTY?

Case studies of transition stages and advice

Many people who have seriously considered reducing typing fatigue have experimented with Dvorak or Colemak and published their results in blogs, forums, and social networks. Here is what the analysis of real cases and independent researchers shows.

On average, it takes one to three months of daily training to switch from the familiar QWERTY to Dvorak. According to researches, in the first two weeks, the typing speed on Dvorak dropped by about half, and the number of typos increased significantly. By the end of the first month, with regular exercises (about 30-60 minutes a day), the user will be able to return to the previous ~60 words per minute and even surpass them, and finger fatigue will significantly decrease.

However, for many users, the most serious issue remains the loss of the QWERTY skill. When you need to type on other people's computers, where the layout does not change, you get a sharp drop in the effectiveness of the muscle memory model.

Colemak has a similar story. It reduces the total movement of fingers by about 2.2 times compared to QWERTY. That is why beginners, having "got used to" the new model a little, really notice a decrease in fatigue.

The main advantage of Colemak its ergonomics and the preservation of familiar hot keys. This makes the adaptation smoother and allows the user to maintain productivity even during the learning process.

Summary

- In a number of open polls on Reddit, users indicated that "reaching the previous speed" on Dvorak takes about 4-6 months of intensive practice (about an hour a day), and on Colemak - about two to three months due to the fact that the scheme has not been changed radically (~20 keys instead of 47).

- In any case, 20-30% of users encounter a huge inconvenience, when switching to someone else’s machine, the speed instantly drops by two to three times, and the number of typos increases in the same proportions.

- Owners of programmable mechanical keyboards (Corne, ErgoDox, etc.) have slightly easier problems with hot keys and macros, since you can pre-load the desired layout and profiles for each OS. Without this, on standard office PCs, one awkward moment with an incorrect Ctrl + Z or Ctrl + V is enough to push off the idea of changing the layout.

In practice, it turns out like this: if you are ready to train systematically (use Keybr, MonkeyType or specialized applications), in a couple of months your speed will return to the "QWERTY level", and then will grow (often by 10-20% higher). At the same time, the load on the wrists and fingers decreases, however, at the cost of the unusable keyboard on any foreign device.

Thus, there is a sense in switching, but only for those who really feel the difference and can compensate for the time spent on training. For the rest, QWERTY remains a universal and familiar tool, despite all its paradoxes and limitations.

What's next for the layout?

Do you think that in five years we will dictate text or type with our thoughts? Not quite. Voice prompts, neural interfaces and "smart" keyboards with LCD keys are not a replacement, but experiments that are not yet ready for mass use.

Voice input and predictive algorithms like GPT prompts already work in mobile applications. You can dictate messages or receive suggestions without touching the keyboard. But in a noisy cafe or on the street, the system begins to hear things that are not there. And in an open space, where salaries or confidential data are discussed, dictation is completely inappropriate. Some things can be voiced, and some cannot.

Programmers, lawyers, writers - everyone continues to type. Because voice does not allow you to quickly edit code, and neural networks do not always understand operators and keywords.

Brain-computer interfaces (BCI) are another promising area, where prototypes already allow recording brain signals and converting them into text. Large companies and startups, such as Neuralink, demonstrate devices that can recognize simple commands and even individual words. Installing a BCI requires complex surgery or inconvenient external sensors, and recognition accuracy is far from ideal. Another important question is how to protect data if an assistant hears your thoughts? On the horizon of 2025, neural interfaces are still laboratory exotics, not a consumer product.

Adaptive "smart" keyboards with LCD keys that can change the display of symbols depending on the context or user statistics were presented in projects by Optimus Maximus, Sonder, Art Lebedev Studio and others. Despite their technological novelty, these devices have not become widespread. High cost, outdated drivers and limited support from software manufacturers have made them a niche product for enthusiasts and designers.

However, the demand for ergonomic and customizable keyboards continues to grow, driven by trends towards individualization and health concerns. As a result, despite the emergence of new interfaces and technologies, the keyboard remains the primary input tool for most professional tasks.

The near future, apparently, is not associated with a revolutionary replacement for QWERTY, but with the evolution of ergonomics, customization and integration of "smart" functions that make working with a keyboard more convenient and healthier.

Support us

Winaero greatly relies on your support. You can help the site keep bringing you interesting and useful content and software by using these options: